Kubernetes Fundamentals

Table of Contents

Interactive Learning Environment

Basic concepts such as Pods, replicas, and different types of Deployment strategies.

All of our labs are powered by Katacoda and are located at this Profile.

Desired State

The declarative model and the concept of desired state is the core of Kubernetes:

- We declare the desired state of our application (microservice) in a manifest file

- POST it to the Kubernetes API server

- Kubernetes stores this in the cluster store

etcdas the application’s desired state - Kubernetes deploys the application on the cluster

- Kubernetes implements watch loops to make sure the cluster doesn’t vary from desired state

Introduction

Kubernetes provides a variety of controllers that you can use to define how pods are set up and deployed within the Kubernetes cluster. These controllers can be used to group pods together according to their runtime needs and define pod replication and pod start up ordering.

Pods

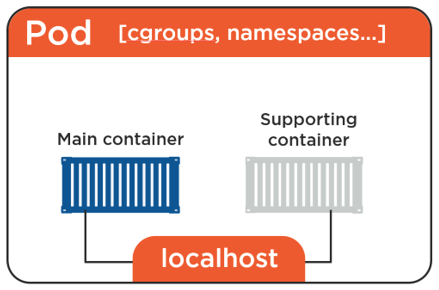

Figure 1: Pod

Yes, Kubernetes runs all sorts of containerized apps (CRI-O, ContainerD, Docker, etc). However those containers always have to run inside of a construct called a Pod. You cannot run a container directly on a Kubernetes cluster.

It can technically be a bit more complicated then that but for now the simplest model is to run a single container inside a Pod. There are some advanced use-cases discussed below where you can run multiple containers inside of a single Pod but for the moment these multi-container Pods are beyond scope.

Examples:

- Service meshes and logging.

- Web containers supported by a helper container that ensures the latest content is available to the web server

- Web containers with a tightly coupled log scraper tailing the logs off to a logging service somewhere else.

A good mental model is to think of a Pod as a ring fenced environment to run containers in. The Pod itself doesn’t actually run anything it is merely just a sandbox to run containers in. Similarly if you ring-fence an area of the host OS, build a network stack, create a bunch of kernel namespaces, and run one or more containers in it then that is a Pod.

Note: If you’re running multiple containers in a Pod, they all share the same environment things like the IPC namespace, shared memory, volumes, network stack etc.

ReplicaSets

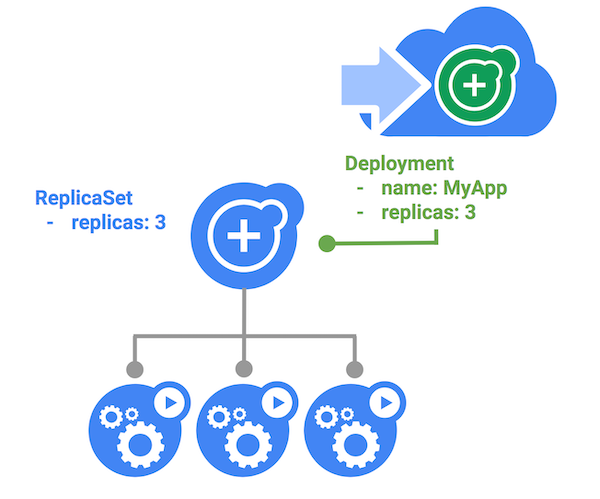

Figure 2: ReplicaSet

You can define a set of pods that should be replicated with a ReplicaSet. This allows you to define the exact configuration for each of the pods in the group and which resources they should have access to. Using ReplicaSets not only caters to the easy scaling and rescheduling of an application, but also allows you to perform rolling or multi-track updates to an application.

A ReplicaSet is a higher-level Kubernetes object that wraps around a Pod and adds features. As the names suggests, they take a Pod template and deploy a desired number of replicas of it. They also instantiate background reconciliation loops that check and make sure the right number of replicas are always running – desired state vs actual state.

Note: Although ReplicaSets can be deployed directly, they are usually invoked by even higher-level objects such as Deployments.

Deployments

You can use a Deployment to manage pods and ReplicaSets. Deployments are useful when you need to roll out changes to ReplicaSets. By using a Deployment to manage a ReplicaSet, you can easily rollback to an earlier Deployment revision. A Deployment allows you to create a newer revision of a ReplicaSet and then migrate existing pods from a previous ReplicaSet into the new revision. The Deployment can then manage the cleanup of older unused ReplicaSets.

Deployments have been first-class REST objects in the Kubernetes API since Kubernetes 1.2. This means we define them in YAML or JSON manifest files that we POST to the API server in the normal manner.

Rolling updates are a core feature of Deployments. For example, we can run multiple concurrent versions of a Deployment in true blue/green or canary fashion. Kubernetes can also detect and stop rollouts if the new version is not working.

StatefulSets

Figure 3: Statefulset

You can use StatefulSets to create pods that guarantee start up order and unique identifiers, which are then used to ensure that the pod maintains its identity across the lifecycle of the StatefulSet. This feature makes it possible to run stateful applications within Kubernetes, as typical persistent components such as storage and networking are guaranteed. Furthermore, when you create pods they are always created in the same order and allocated identifiers that are applied to host names and the internal cluster DNS. Those identifiers ensure there are stable and predictable network identities for pods in the environment.

DaemonSets

Figure 4: Daemonset

DaemonSets manage groups of replicated Pods. However, DaemonSets attempt to adhere to a one-Pod-per-node model, either across the entire cluster or a subset of nodes. Daemonset will not run more than one replica per node. Another advantage of using Daemonset is, If you add a node to the cluster then Daemonset will automatically spawn pod on that node, which deployment will not do.

DaemonSets are useful for deploying ongoing background tasks that you need to run on all or certain nodes, and which do not require user intervention. Examples of such tasks include storage daemons like ceph, log collection daemons like fluentd, and node monitoring daemons like collectd.